How did I get into urban agriculture?

One of these heads is not like the other - Brightbox - Venlo, Netherlands

There was no single defining event that led me to join the urban agriculture/agtech industry. Rather, it was the circumstances of my childhood and a series of events that formed this journey of the last five years. And with any good story, it starts with a character of inspiration. In this story, it is my grandmother.

Within the first month of my existence on Earth, my parents flew me from New York all the way to South Africa to meet my grandparents. This would be the first of dozens of trips to South Africa to visit our family who resided on the Cape Peninsula mountains. It was at my grandmother’s house where I was first exposed to the breathtaking flora and fauna of the Western Cape.

Hydrangeas in the garden

Every year when we went to visit, I was greeted by this beautiful garden, this kaleidoscope of colors, as we walked past the front door. Bursts of purple and pink hydrangeas terraced across the property. Herbs, veggies, and fruit sprouting throughout the backyard. Bags of soil, clay pots, and garden tools were scattered across the garden shed. Even now, I can still recollect climbing the stairs of the garden, the hydrangeas towering over me, to the raised beds to pluck the carrots from the soil and the strawberries from the vine. A joyous moment then. A defining moment now.

Stateside, South Florida was not a place where my friends or I lived on a farm or remotely close to a farm. The urban sprawl of suburban life doesn’t lend itself well to the agrarian economy. However, the subtropical climate does provide quite the conditions for fruit trees to thrive. Florida avocados, grapefruit, mango, lemon, lime, litchi, passion fruit, and banana trees are what was rooted in my yard.

Two mango trees & a chocolate lab

These fruit-producing trees were the gem of our property. Grapefruit for breakfast. Mangos for dessert. And the rest mixed in between meals, recipes, or left for the soil where nature would do what it does, decomposing back to the ground. On weekends, my mother would treat us by taking a trip just north to Bloods’ Grove. A 100-acre citrus grove run by four generations of the same family. It was here that my taste buds would ride a rollercoaster of flavor. Sweet. Tart. Sour. Ruby red, white, orange, yellow. Honeybells, white grapefruit, tangelos, mangoes, and more. Some kids folks would take them to the candy store. My parents took me to the local citrus grove.

Then, in 2002, our citrus trees had to be cut down. An outbreak of citrus canker, a bacterial disease, started spreading throughout South Florida, threatening decades of citrus growth, citrus producers, and citrus owners. It was a knock at the door by the local county agriculture department that notified my family that our citrus trees were slated by county order to be cut down due to the department's policy stating that any citrus tree within 1,900-feet of an infected area would need to be cut down to mitigate the spread of canker. Damn. The loss of this fruit-producing tree impacted me in a way that only later in adulthood did I start to understand.

At the end of my senior year of high school, I came across a blog post in class about vertical farms. Featuring Dr. Dickson Despommier, “The father of vertical farming”, this post discussed the futuristic skyscrapers that could one day tower over our cities producing pounds and pounds of produce. It illustrated the different kinds of farms interlaced between each floor, growing different types of produce, integrating black, gray, and freshwater from city reservoirs creating this recirculating system. Waste in, food out. The vision- that a city could be a producer, not just a consumer. Another seed planted in my head about the role urban agriculture and technology could play in our cities. These ideas would linger in my mind all the way through college, making appearances over the next few years that would further connect the technological component of agriculture to the urban setting.

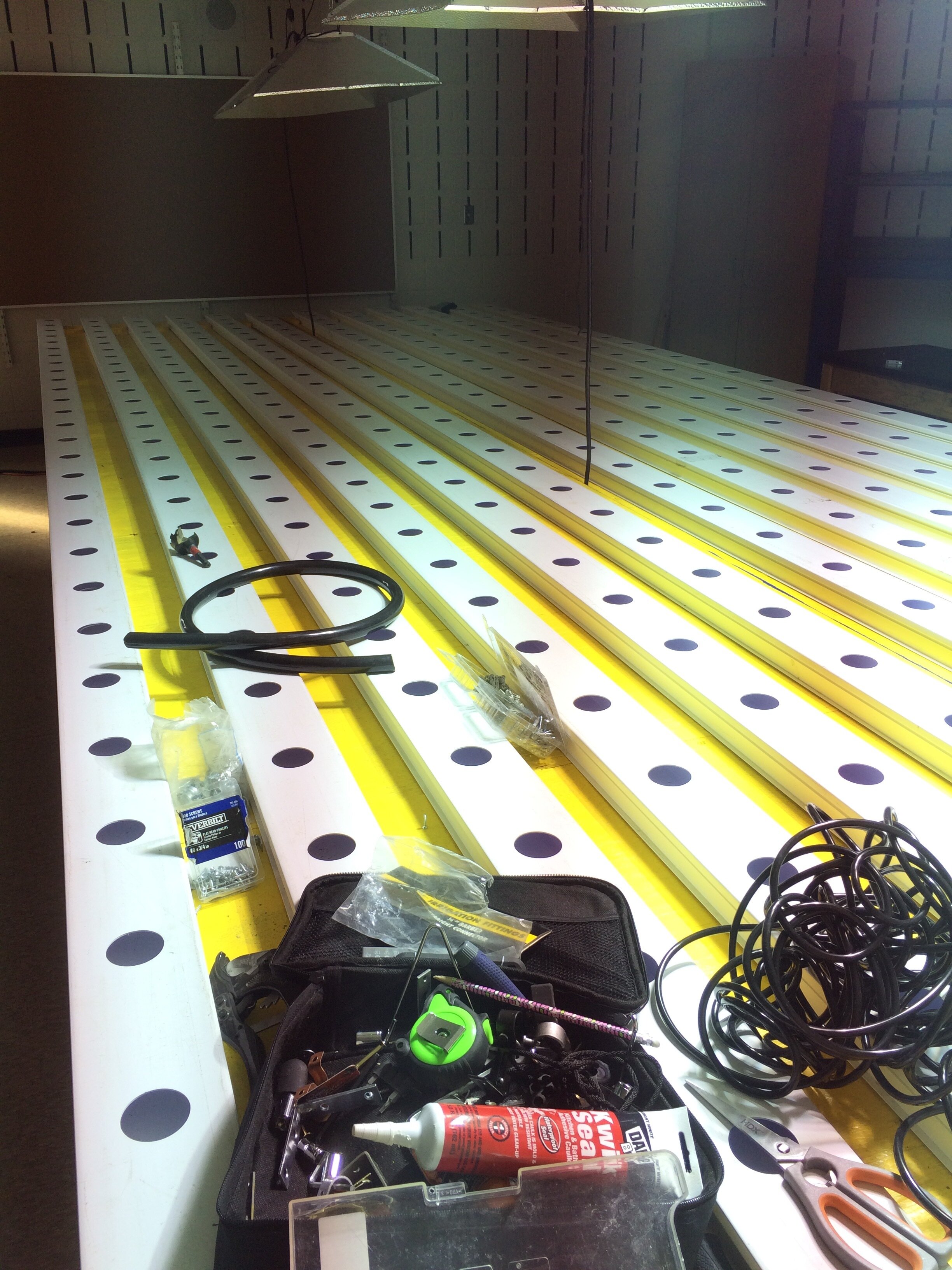

At Georgia Tech, the seeds took root. I caught sight in the local newspaper of an interview with the executive director of a non-profit discussing their mission to build hydroponic systems in elementary schools around the metro-Atlanta area to further children's understanding and connection with how food was grown. My time volunteering at this non-profit gave me my first experience building the nutrient film technique (NFT) systems. This mentor provided my student club, Engineers for a Sustainable World (ESW), with growing systems of our own to tinker and test inside a small rooftop greenhouse on top of our biology building. And it was this mentor that introduced me to a local retail hydroponic store where I began working part-time.

I spent my Sundays coming into the store to review inventory, assist customers, make sales, and soak in the vast amounts of knowledge about hydroponics. At this store, the horticulturalist, David Kessler, introduced me to the blog, Agritecture. From the moment I learned that URL, I was hooked. Vertical farms. Hydroponics. Urban agriculture. Startup companies and the latest agtech news. This was my rabbit hole for all things urban agriculture and agtech. It was information overload, and I could not get enough.

Agritecture was the knowledge tool I leveraged when my club, ESW, entered into a design competition at Georgia Tech focused on sustainably renovating campus buildings. We pitched a hydroponic growing unit for all our residence halls.

We won.

Agritecture was the resource I used with my senior design capstone team to design a modular, stackable hydroponic unit for home users, New Leaf.

Team New Leaf at Georgia Tech Capstone Design Expo

We did not win this one.

Agritecture was my daily read when I searched for a full-time job after college in the urban ag/agtech scene. And it was Agritecture that announced a year and a half after graduation that it would be hosting a public design competition at Georgia Tech with the Father of Vertical Farming, Dr. Dickson Despommier, as one of the lead judges.

Between graduation and this workshop was bumpy. I couldn’t find a job in the industry due to the lack of experience in farming/agriculture and the juniorness of my engineering career. I decided to return to Delta Air Lines to work in their 24/7 structural engineering support team. But I knew this wasn’t going to be it for me. Before going back to Delta Air Lines, I spent several weeks in Australia WWOOFing on a small farm which further reinforced my desire to work in agriculture.

I returned from Australia, started at Delta, and picked up a volunteer writing position for the Association for Vertical Farming, researching academic institutions and the lack of horticulture programs needed for the industry. When I wasn’t on-the-clock at Delta, I was reading, writing, and networking on all things urban ag, vertical farming, and greenhouses. So much so that by the time I got to the Agritecture Workshop at Georgia Tech, I was one of the most knowledgeable participants there. At this workshop, I led my team through a 2-day design charade. At this workshop, I presented to the “Father of Vertical Farming” himself! And at this, workshop I was able to come face to face with the team at Agritecture and show how excited and serious I was about this industry.

We did win this one.

And from here, I became the first full-time employee at Agritecture. A company that has opened up my world to the incredible technologies and innovations that are reshaping the role agriculture plays in our cities.

So when someone asks me how I get into urban agriculture, I have to tell them that it wasn’t one singular decision or event that brought me here. Instead, it was a series of events that compounded over time, putting me in the right place at the right time. And if you’ve made it this far, I’ll let you know that I later discovered that when registration opened up for that Agritecture workshop, I was the first person to sign up.

Go figure.